Dec. 9, 2020

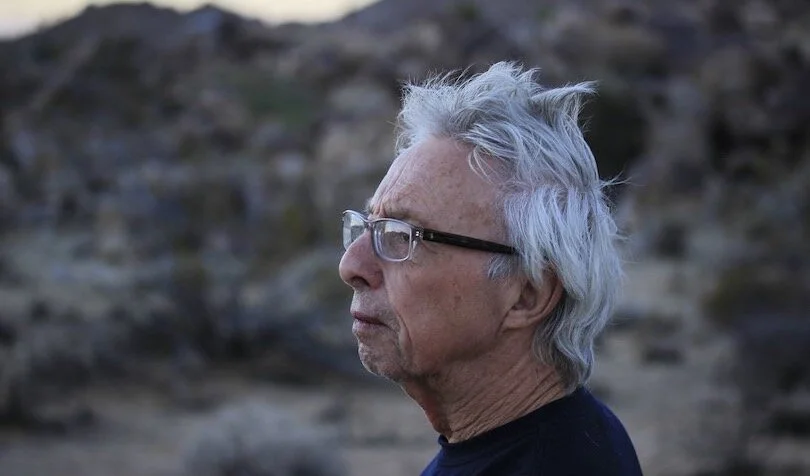

Another day, another musical icon gone. Composer Harold Budd has left us at age 84, thanks to complications from COVID-19 which he contracted while recovering from a stroke (as per Bill Nelson’s moving tribute).

I swear I never intended for this blog to become a mausoleum, or for this One Song game to just be a series of memorials to the departed. But it seems 2020 isn’t done brutalizing us, and I’m just dealing with what it’s throwing at me. So here we go with a new round of One Song that doubles as a eulogy.

Probably like most people my age, I discovered Harold Budd through his 1978 album The Pavilion of Dreams on Brian Eno’s Obscure Records label. The tenth, and as it turned out, final release in the series, it was really not much like anything else on the label, not least of all because it was by an American. (The only other Yank on the label was John Adams, before he found his mature style and became the John Adams.) The music was diaphanous, unapologetically gorgeous – all tinkling celesta, warm marimbas, harps, and female chorus, with just a whiff of jazz thanks to a somewhat surprising appearance by free jazz saxophonist Marion Brown. At a time when Steve Reich and Philip Glass were all the rage, it was the kind of record that made me scratch my head. But I couldn’t deny the beauty, or turn away from it. Where did this come from?

It turned out that Harold had already done the minimalist thing on his previous album, 1971’s raga-esque Oak of the Golden Dreams – the title track on Side 1 is a fat synth drone embellished with lacy melodic filigree, and Side 2’s Coeur d’Orr explores similar terrain but with pipe organ and soprano sax. But that album was truly obscure – as in, very few copies pressed on a tiny boutique label that almost nobody heard – and as he later said, he felt he’d painted himself into a minimalist corner. The Pavilion of Dreams was his counter-move away from the repetitive structures of minimalism and the intellectual complexity of academic music, and towards the militant embrace of something more flagrantly sensual, intuitive, and lush. He strove to make music that was shamelessly decorative, concerned with surface and clarity, perhaps echoing the work of certain other Southern California visual artists, such as Robert Irwin, James Turrell, or Larry Bell. This shift required a certain kind of courage, and if it meant he no longer had a place in the avant garde or in the world of so-called “serious music,” so be it.

A few years later Harold reappeared on Eno’s new Ambient series. They did two records together, both now regarded as classics: The Plateaux of Mirror and The Pearl, the latter with a then-unknown Daniel Lanois. But Eno’s notion of ambient music eventually grew legs and became its own genre, which in turn was easily confused with New Age music, and Harold resented being lumped in with all of that. Beneath the surface of that congenial aesthete lurked the soul of a cantankerous desert rat.

From then on his career became somewhat less predictable. He went back to releasing albums on various independent record labels, and working with a wide range of artists. Some of those were in the classical world, such as the ensemble Zeitgeist. Some were in the popular music scene, such as the Cocteau Twins, Hector Zazou, John Foxx, Andy Partridge, and David Sylvian. I personally find a lot of Harold’s post-Eno work to be uneven, but I admire his willingness to put himself in situations that led him to unexpected places.

Budd is often thought of as having something to do with electronic music, but I think the reality was that the electronics were largely the imprint of his collaborators. Harold liked the sounds they got from him, but he was really a pianist at heart, and you can hear no better example than La Bella Vista, an album of improvised piano solos recorded by Daniel Lanois without Budd’s knowledge.

In addition to his own music, Budd leaves an important legacy through his students at Cal Arts in the 70s who then went on to forge their own post-minimalist approaches in his wake, many of them associated with the Cold Blue record label – composers like Jim Fox, Chas Smith, Daniel Lentz, Michael Jon Fink, Peter Garland, John Luther Adams (not to be confused with the John Adams mentioned earlier). Budd’s influence can be detected to varying degrees in the work of all of them, not to mention that of younger artists who grew up on Ambient as a sub-genre of electronic dance music and eventually found their way to Budd as a revered Old Master.

I first met Harold when I presented him in Albuquerque, in a duo concert with Jon Gibson (who, sadly, also passed away recently). He was incredibly gracious and unpretentious, the kind of California guy who would unironically say things like, “Far out, man!” We stayed in touch over the years, and when I moved to Seattle I overheard someone in a used bookshop saying they were about to publish a book of his poetry and were planning to have him come to Seattle to do a reading to launch the publication. We then set about arranging a concert at the Chapel as an extension of the reading, and Harold played in a duo with local bassist Keith Lowe. It was so gratifying to hear Harold’s distinctive piano sound coming out of our vintage Knabe concert grand. Such a pleasure. You can hear a bit of that 2009 concert here.

A few years later (2012?) Mary and I celebrated our anniversary with a trip to Joshua Tree with some friends from Los Angeles. The first night we were there, as we pulled up to the Crossroads Cafe for some dinner, I mentioned to them that I’d heard Harold was living in Joshua Tree. It’s a small town. Wouldn’t it be funny if we ran into him? Sure enough, when we entered the restaurant he was standing in line right in front of us, and we ended up having dinner with him. He invited Mary and I to come to his house a few nights later for some wine and conversation. Both were thoroughly enjoyable. And that was the last time I saw him.

As for choosing one essential song, I’m surprised at how easy it was given the extent of his catalog. But for the past few years, whenever I’m in the mood to hear Harold’s music I tend to gravitate toward this dreamy hour-long masterpiece. Technically this is a remix of fragments taken from other pieces on his Avalon Sutra album, made by the brilliant Akira Rabelais. Whoever gets the credit, it’s a stunningly beautiful immersive piece that I can live in for days. So click Play and drift away.